Thumbs Up to Success: Mastering the CMC Joint

An Interview with

— Mr. Alistair Jepson —

Issue 03, August 2023

Can you explain the role of the CMC joint in hand function and its importance for daily activities?

The thumb is anatomically unique when compared with the other digits of the hand. Not only does it have just two phalanges, but it also differs in having more freedom of movement and being able to work with, or against, the other digits (this is termed opposition).Opposition is what allows humans a greater ability to manipulate objects and perform actions such as pinching or grasping, when compared with primates and other animals. Consider opening a bottle or tying your shoelaces without your thumb and you quickly realise its worth.

The unrivalled dexterity of the thumb is derived from the joint at its base - the Carpo-Metacarpal (CMC) joint. This is often described as a saddle shaped joint because of its appearance of two saddles coming together at 90° angle. These two opposing surfaces give rise to its wide range of motion, but with pinch and grasp come high joint reactive forces – for example, a force up to 12 times greater in the CMC joint than at the tip of the thumb with pinch, and compressive forces of as much as 120 kg with forceful grasp. The thumb CMC joint, therefore, requires strong ligaments and tendons, working in unison, to maintain stability, as well as the unique bony architecture of joint.

What are the most common causes of CMC joint arthritis, and what symptoms do patients typically experience?

The thumb CMC joint is unfortunately a common site of osteoarthritis, being second only to distal interphalangeal joints in the hand. The reasons for this seem to be multi factorial:

- Like other joints the incidence increases with age(significant increase over the age of 50)

- High body mass index has a direct correlation.

- Previous fractures and dislocations of the thumb predispose the thumb to osteoarthritis, as do.

- Some occupations, especially those involving repetitive thumb movements, such as builders.

What is more unique though about the thumb is the fact that women are 10-20 times at higher risk of osteoarthritis than men; this disparity is thought to be due to a hormonal difference between the sexes which in turn affect ligament and joint laxity, with degeneration of the anterior oblique beak ligament of the CMC joint being the usual precursor of basal thumb arthritis.

Could you discuss the different treatment options available for CMC joint arthritis, including both surgical and non-surgical approaches?

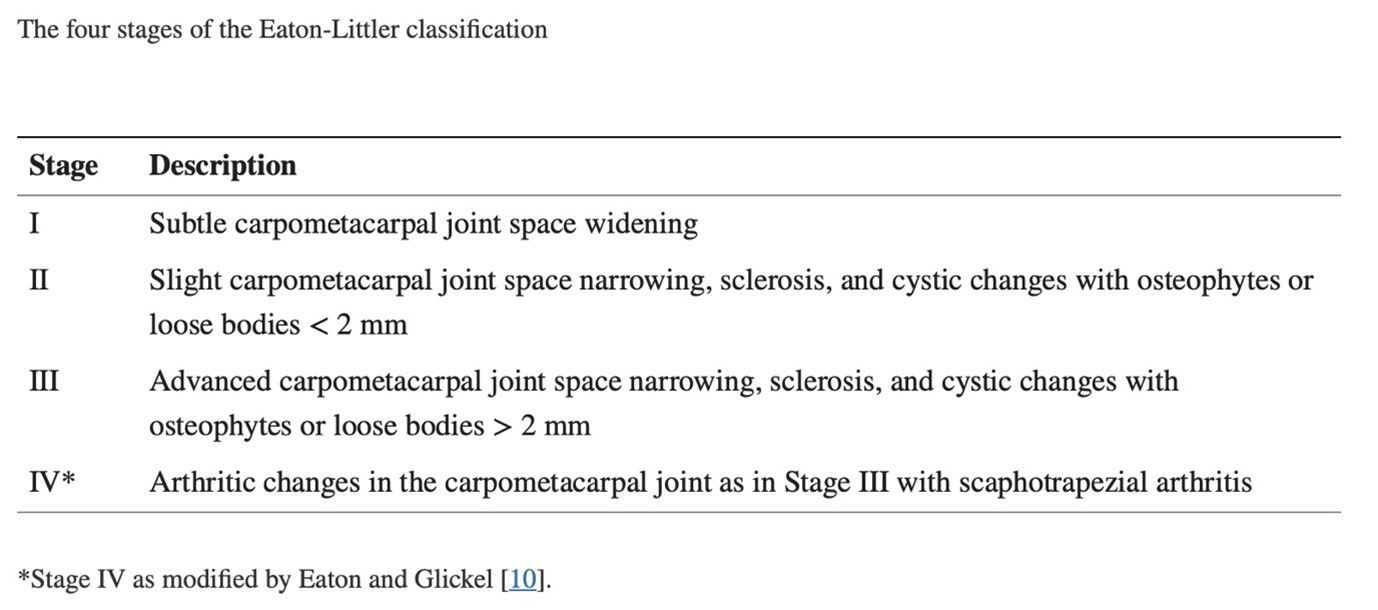

The treatment that I would offer a patient would depend on their symptoms, their functional deficits, and the stage of their arthritis, with the Eaton-Littler classification being used to grade basal thumb arthritis.

Non-surgical management would always be first in mind, including activity modification, pain relief, splinting, and hand therapy. The next likely step would be an image guided joint injection with steroid, but in a younger patient I might offer a hyaluronic acid injection,, and some surgeons might offer a Platelet Rich Plasma injection.

Surgical options for thumb CMC joint arthritis are varied. Trapeziectomy, first described by Gervis in 1949 has become the most commonly performed operation over the years, with subsequent modifications to include ligament reconstruction with or without tendon interposition (the so called LRTI). Other options include fusion, resurfacing arthroplasty, silicone arthroplasty, and total joint replacement; each having their own advantages and disadvantages.

Trapeziectomy +/- LRTI was the procedure I was brought up with while training, but, like many other colleagues, I found the recovery to be long and unpredictable from this operation. I have also seen many younger patients referred to me with problems after trapeziectomy, predominantly issues with weakness of pinch and grasp, but sometimes also instability; such patents are incredibly challenging to treat with no good reliable surgical option.

This is why, for me, total joint replacement of the thumb CMC joint has become my operation of choice for basal thumb osteoarthritis; not only is recovery significantly quicker, but the restoration of strength and range of motion is much more predictable, and furthermore should complications develop I believe these to be easier to address.

Total joint arthroplasty of the thumb CMC joint has come a long way since the 1st generation cemented implants of the early 1970’s (e.g., de la Caffinière® implant). Subsequent innovations have been to switch to uncemented implants with hydroxyapatite coated cups and stems (e.g. Arpe® and Ivory® implants), and now the current 3rd generation implants have dual mobility, allowing better arc of movement, better stability, and reduced loosening compared to single mobility e.g. the Maia® and Touch® prostheses.

What types of imaging or diagnostic tests do you rely on to assess the condition of the CMC joint and determine the best course of treatment?

A recent set of plain x-rays of the thumb is essential, and where there is a concern on those x-rays about the height or width of the trapezium, or the presence of a large bone cyst or one of both sides of the joint, I would request a CT scan with 3D reconstructions.

Sometimes an MRI or USS can prove useful if there are concerns about another diagnosis, e.g., de Quervain’s or STT joint problems. I would point out though that should the STT joint appear radiographically arthritic then this would not necessarily exclude a CMC joint replacement, but it would mean usually further assessment was required with a diagnostic injection to determine if the arthritis was symptomatic or not.

How do you determine whether a patient is a suitable candidate for CMC joint replacement surgery?

I believe almost all patients who have failed non-operative treatment are suitable for a CMC joint arthroplasty with a few exceptions. The exceptions are where there is insufficient trapezium to secure the cup in the trapezium (standard trapezial cups are 9mm and 10mm, but 8mm cups are available for smaller trapeziums). Symptomatic STT joint would be another potential contra-indication, as would the fear of premature implant failure in someone with a very manual job, and there is some controversy about whether a CMC joint replacement should be done in a more elderly patient, given the high cost of the implant, and potentially osteopenic bone.

What are the main goals and expected outcomes of CMC joint replacement surgery?

A thumb CMC joint replacement differs from other options for treating basal thumb arthritis, in that it both preserves the length of the thumb and it provides an articulation which, whilst not saddle shaped, almost fully replicates the movement of the native thumb; hence strength and range of motion are maintained with a replacement. The inherent stability too of the dual mobility implant allows for an accelerated recovery, without the need for significant immobilisation, just a splint for comfort.

- Rapid relief of pain

- Quicker recovery

- Better recovery of strength

- Better recovery of mobility

- Preservation of joint stability

- Preservation of thumb length

- Improved aesthetic appearance

Are there any alternative surgical procedures or techniques for CMC joint arthritis that you have found to be effective?

Prior to arriving on the Touch® and Maia® 3rd generation implants I tried a number of other options in younger patients, including two types of hemiarthroplasty and one interposition arthroplasty, all utilising pyrocarbon. Some of these worked very well, but the results were not consistent, and the indications limited to a reasonably concentric joint i.e., no subluxation or dislocation.

The results from the 70+ replacements I have done over the last five years have been so good that I would not consider any other arthroplasty option presently.

How do you address patient concerns and manage their expectations when it comes to complex procedures?

A thorough balanced explanation of both the expected benefits of the operation and the possible risks is essential. Equating a thumb CMC joint replacement to an upturned microscopic hip replacement is usually the first part of my explanation, as this is something most patients will understand. The second part is to discuss recovery after surgery, time off work and likely time away from hobbies etc.

The specific risks I tend to explain in detail are:

- Infection - this though is very rare for the thumb, and is certainly a lesser risk than with hip, knee and shoulder arthroplasty, presumably because of the different skin flora on the hand, compared with the skin flora of the axilla (for shoulder arthroplasty), and the groin (for hip and knee arthroplasty). I have to date had no deep joint infections, just one superficial infection.

- Numbness - this is common due the close proximity of the superficial radial nerves – it fortunately resolves after about 2-3 months.

- Instability and dislocation – I have had no cases to date.

- Loosening - I have had no cases to date.

- Intra-operative fracture of the trapezium - I have had no cases to date.

- De Quervains tenosynovitis - I have had one case, which resolved with a steroid injection. Some colleagues I know routinely release the 1st dorsal tendon compartment during their surgical approach to avoid this complication.

Can you share some insights on the recovery process after CMC joint replacement surgery, including the timeline and rehabilitation exercises?

It is hard to accurately quantify the speed of recovery of a CMC replacement compared with a trapeziectomy, but I would estimate the recovery to be around 50% quicker. Most patients are already happy with their implant at their first review 2-3 weeks after surgery, and most can be discharged at 3 months post-surgery. Occasionally patients do take longer to recover, and I believe this is commonly due to pain and swelling, and other times patient compliance.

Are there any specific precautions or lifestyle modifications that patients should follow after CMC joint replacement surgery?

I would be very cautious about performing a CMC joint replacement in someone with a heavy manual job, and for the same reasons after a replacement I recommend avoiding repeated heavy tasks, but other than that almost no lifestyle modifications are needed.

How long do the results of CMC joint replacement surgery typically last, and are there any factors that can affect the longevity of the implant?

So far results have been published for single mobility implants for in excess of 10 years and dual mobility for nearing 10 years.

Are there any advancements or emerging technologies in CMC joint surgery that you find promising?

None I am aware of, but I anticipate implant choices will evolve to include the potential to make revision surgery easier; retentive cups are already available for instability with single mobility implants, a conical shaped cup is an option with the Touch® prosthesis, and I suspect other modifications of cup design will become available for revision surgery.

What advice do you have for patients who are considering CMC joint replacement surgery but may have concerns or fears about the procedure?

A thorough explanation of the operation and discussion about both benefits and risks is essential. I always explain to patients it is a relatively new implant and I can’t predict how long their implant will last but that it reasonable to expect theirs to last >10 years. Furthermore, if a patient was very anxious or undecided, I would put them in contact with a patient who had previously had the operation.

Can you discuss the importance of post-operative follow-up care for patients who undergo CMC joint replacement surgery?

Rehabilitation following a CMC joint replacement is an area where little has so far been published. In my own case I learnt a lot from the first replacement I did in 2018. Post operatively I immobilised the patient in a plaster backslab but within a few days of surgery the patient reattended saying they couldn’t bear the plaster and could I remove it, which I did with some trepidation, but I then witnessed the remarkable speed at which a patient with a CMC joint replacement could recover; consequently I have since stopped immobilising patients in plaster, I now just a soft wool and crepe for 5 days. The hand therapists then see the patient to make a thumb-based splint, which is worn for comfort and protection for perhaps 3-4 weeks.

Are there any specific patient demographics or characteristics that may influence the choice of treatment for CMC joint arthritis?

I would prefer to offer a thumb CMC joint fusion in a patient with a very physical job. I have previously alluded to age being a potential factor too.

How do you stay up to date with the latest advancements and research in the field of CMC joint surgery?

Despite 5 years’ experience I continue to advise all my patients that this is a moderately new procedure and that long term results are not yet available. I also strongly believe in data collection and understanding outcomes, so since starting I have collected outcome scores preoperatively and at 3 / 6 / 12 and 24 months post operatively (QuickDASH, VAS and EQ-5D scores).

I also strongly believe in education, and I have been invited as Faculty by LEDA on the Maia thumb CMC joint replacement course and I have also taught the fellows we have at Northampton as well as supporting consultant colleagues new to the procedure.

Finally, what inspired you to specialise in orthopaedic surgery, particularly in the treatment of conditions affecting the hand and upper limb?

The complexity and intricacy of hand & wrist surgery has always interested me, and I have been fortunate to have amazing mentors both during my training program in North West Thames and on fellowship, in the Brisbane Hand & Upper Limb unit and at the Pulvertaft unit in Derby.

About Mr Alistair Jepson

Mr Alistair Jepson is a highly trained and skilled consultant orthopaedic surgeon based in Northamptonshire. As a specialist in upper limb surgery, he provides professional and personalised surgical care for shoulder, elbow, hand and wrist conditions.

Mr Jepson graduated from the University of Birmingham in 1994. After this, he trained in and around London, with his orthopaedic specialist training taking place within the North West Thames region. He attained specialist accreditation in 2004 and then pursued his interest in upper limb surgery with two fellowships: the first being an upper limb fellowship at the Princess Alexandra Hospital in Brisbane, Australia (one of the largest and busiest upper limb units in the country) and the second being a hand fellowship back in the UK at the Pulvertaft Hand Unit in Derby.

His work is dedicated to providing the best possible outcomes for patients in both the public and private health sectors. What's more, his confident diagnostic skills are matched by his surgical expertise and meticulous explanations at every step of any procedure. His NHS practice is based at Northampton General Hospital, and privately he consults at the Three Shires Hospital in Northampton, the Ramsay Woodland Hospital in Kettering, and, by arrangement, at the Harley Street Specialist Hospital in London.

We would like to thank Mr Jepson for his time and insight into CMC joint replacement and overall contribution to the August edition of On The Podium.

To read more about Mr Jepson's practice visit upperlimb.co.uk

To download this issue of On The Podium, click below.

Sign up to On The Podium. The latest insights and inspiration from orthopaedic specialists around the globe sent straight to your inbox.

On The Podium

The newsletter brought to you by OrthoSpaceX

| Engage with Orthopaedic Leaders | Exclusive orthopaedic insight | |

| Stay Ahead in Orthopaedic Advancements | Uncover Surgical Innovations | |

| Empower Your Orthopaedic Knowledge | Unlock the Minds of Orthopaedic Specialists |