The CTC (“Closing the Circle”) Technique

An Innovative approach to treating AC Joint Stabilization

An Interview with:

— Ana Catarina Ângelo —

Issue 07, February 2024

What initially drew you to pursue a career in orthopaedic surgery, and what motivated your decision to specialise in shoulder and elbow surgery?

Well, since the beginning of medical school I always wanted to pursue a surgical career. I like intervention, and the act of physically correcting something that is wrong fascinates me. When I was in the last year of medical school I fractured my tibial plateau and that unexpected contact with the orthopedic reality made me realize that O&T was the right choice for me. Also, I quickly realized that this specific surgical field was evolving a lot, with new understandings and new techniques, and I personally like the idea of being part of the evolution of my field. Shoulder and elbow was love at first sight. The biomechanics of the shoulder girdle fascinated me and the “unknown” elbow world was a super appealing challenge. I decided to become a shoulder and elbow surgeon in the second year of my residency. This made me super focused on this specific subject since the beginning. I started attending a lot of advanced courses very yearly to develop my technical and theoretical skills. When I finished my residency, I already felt very comfortable in the majority of the surgical procedures and with the theory behind them. A super important point is that I’m lucky enough to work alongside my partner Prof. Clara Azevedo, who highly contributed to my steep evolution in this field.

Could you share some of the most rewarding moments and challenges you've encountered in your journey as a shoulder surgeon?

For sure. My journey has been marked by some challenges but, luckily, the balance is highly pending to the rewards side. Obviously, the fact that I am a woman brought me some challenging moments when I started my career in a still very masculine field like O&T. But I had a lot of support from senior female surgeons in my department and this aspect quickly became a non-issue.

When I chose to focus on shoulder and elbow in a very early phase of my residency I was criticized, and for a few years I struggled with keeping up with my goals. But honestly I would do it all again, exactly the same way. Resilience is important in our field, and learning how to deal with criticism and failure is a must if you want to be a successful surgeon and scientist. This takes me to my first publication in a Q1 peer-reviewed international journal, which is definitely one of the most rewarding moments of my career. When Clara and I published our first results regarding SCR (superior capsule reconstruction) and donor site morbidity associated with our harvesting technique I felt like I was finally leaving my footprint in the amazing field of shoulder surgery. What a feeling. Our careers have sky-rocketed since then and it has been an extremely rewarding journey. Getting to know, befriend and exchange ideas with the best "shoulder and elbow minds” from all around the world is priceless. This is my biggest reward and I wouldn’t trade it for a calmer and less stressful life.

Looking ahead, what are your aspirations and goals within the field of shoulder surgery, both in terms of advancing clinical practice and contributing to research and education in the field?

Well, I feel very excited with what I see coming ahead. Generally, my goals focus on continuing research regarding the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears and the role of superior capsule reconstruction using a fascia lata autograft. This technique has been highly misinterpreted in the literature, mostly due to the introduction of several allografts that are not ideal and produce inferior results. We have a good pool of patients and we’re beginning to have a long follow-up that will allow us to better understand how this technique can influence the natural history of irreparable rotator cuff tears. Another field that we aspire to somehow improve is the treatment of anterior glenohumeral instability using a new and interesting soft tissue technique called DAS (dynamic anterior stabilization). This reproducible technique theoretically allow us to treat patients with limited to subcritical glenoid bone loss using only soft tissue, while adding stabilization effects that were previously only obtained with bony procedures. The preliminary results are very good, but, like with any technique, it still needs to pass the test of time. So, we’ll keep following our patients to find out if this technique works in the long run. Finally, the CTC technique is also one of our main present and future study subjects. We developed the CTC do address some problems and probable causes of failure that we encountered in our practice and in the literature regarding the surgical stabilization of the coraco-acromio-clavicular complex. We started doing it in 2018 and we plan to review our pool of patients and statistically and clinically assess the mid-term results.

Can you elaborate on your "Closing the Circle" technique for acromioclavicular joint stabilization and how it addresses the tridimensional stability of the joint?

As I said before, we felt the need to design this technique to address some insufficiencies of the techniques that we previously used. AC joint stabilization techniques have a high failure rate mostly due to the fact that for many years there was an insufficient knowledge about the biomechanics of the AC joint complex. Treatment modalities were very focused on reestablishing vertical stability in one plane, and this would only make sense in low grade lesions (Rockwood I, II and IIIA) in which conservative treatment is highly successful. In high grade lesions there is usually a compromise of both CC and AC structures as well as a tear in the deltotrapezial fascia. This usually results in a tridimensional instability - vertical, horizontal and rotational. To correct this complex instability we should address the 3 planes of motion, which is impossible to achieve with a single implant that reconnects the clavicle to the coracoid in one plane. Our goal was to design a technique that allowed us to recreate the biplane vertical stabilization of the conoid and trapezoid CC ligaments, while also addressing the AC joint ligaments and capsule and the deltotrapezial fascia. To minimize complications related to metallic implants and wide bone tunnels we replaced the subcoracoid buttons by 2.8mm all-suture anchors that actually work like “soft tissue buttons”, and we use the 2.9 drill to pass the anchors and the sutures through the coracoid, the clavicle and the acromion. By placing 2 anchors in the coracoid, one double-loaded and one triple-loaded, we are able to reconnect the coracoid to the clavicle in 2 vertical planes, mimicking the trajectory of both CC ligaments, and also to cerclage around the ACjoint using sutures coming from these same anchors. The AC joint is stabilized in an "open figure of 8” fashion, theoretically allowing clavicular and acromial rotation without compromising horizontal stability. We perform this technique through an open approach which allows us to properly repair the AC capsule and the overlying deltotrapezial fascia. It is very important to mention that this technique has been designed for acute high grade AC joint injuries (up to 3 weeks after trauma).

What biomechanical principles underlie your approach to addressing both vertical and horizontal instability in AC joint dislocations?

The role of horizontal stabilization in the treatment of high grade AC joint injuries has been extensively studied in the last 20 years. But actually, in 1986, Fukuda and colleagues (Fukuda K, Craig EV, An KN, Cofield RH, Chao EY. Biomechanical study of the ligamentous system of the acromioclavicular joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986 Mar;68(3):434-40. PMID: 3949839.) had already established that the acromioclavicular ligaments and capsule played a crucial role in the posterior displacement and posterior axial rotation of the clavicle. In the early 2000 the group of Richard E. Debski from the university of Pittsburgh published a biomechanics cadaveric study in which it the authors concluded that both the AC capsule and the 2 coracoclavicular ligaments help to resist translation during application of external loading conditions in the posterior, anterior and superior directions, but in different proportions. This means that during range-of-motion there’s a complexity of restraining forces that work together and in varying proportions to maintain tridimensional stability of the coracoacromioclavicular (CAC) complex. The CTC technique was designed to recreate the spheric structure of this anatomical complex to be able to accommodate all translational forces involved during full ROM.

How does your technique consider the complex anatomy of the AC joint and its relationship with the coracoid process in achieving stability?

The CAC complex connects the clavicle to the scapula in 3 distinct points: 1) the AC capsule and ligaments; 2) the trapezoid ligament; and 3) the conoid ligament. These 3 connection points have different shapes and vectors that correlate with their specific biomechanical role as AC joint stabilizers. The CTC technique also involves 3 connection points – 2 vertical coracoclavicular connections with different vectors to recreate the conoid and trapezoid roles, and a figure of 8 around the AC joint to simulate AC capsule and ligaments.

Could you share a case study or example where you successfully applied your technique, and what were the outcomes observed in terms of joint stability and patient recovery?

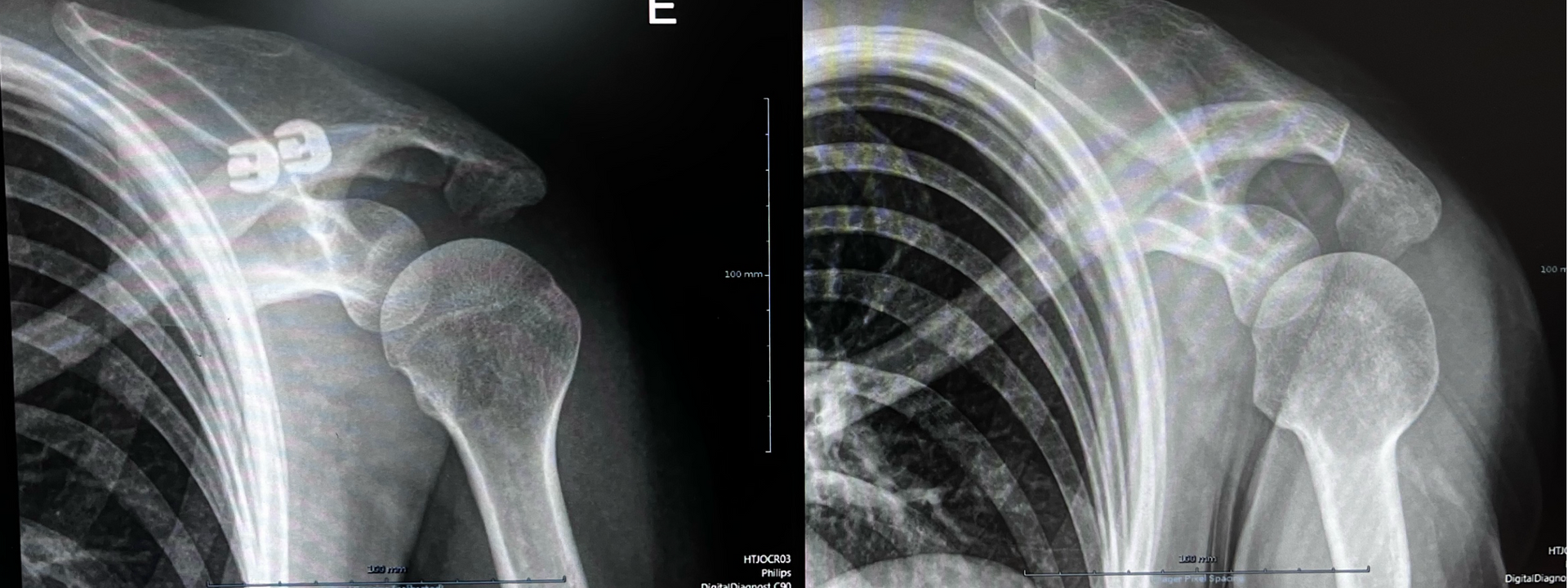

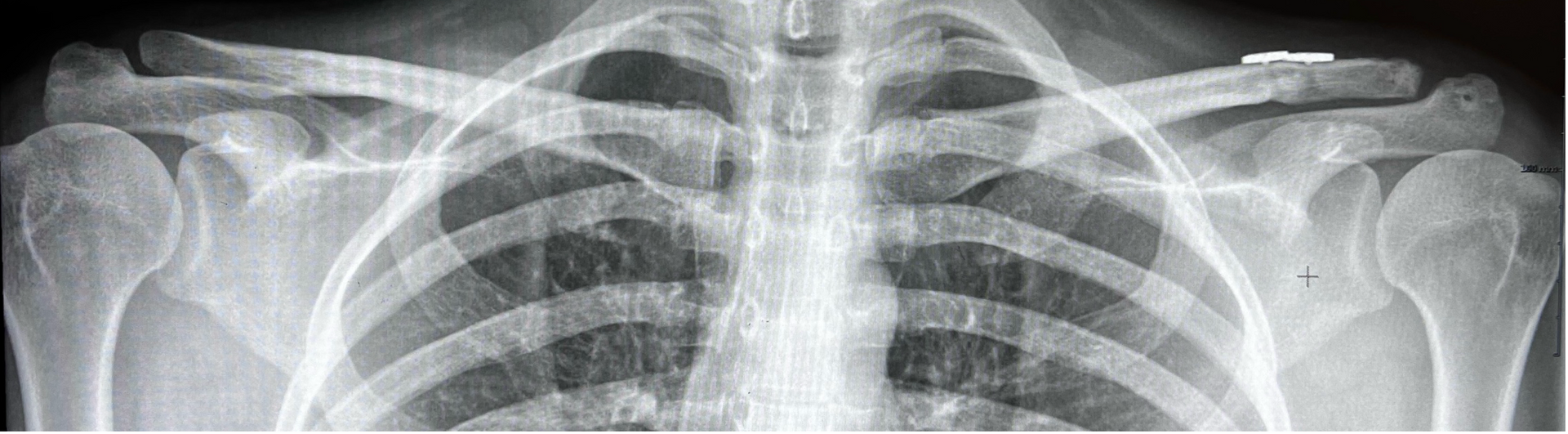

Of course. So, this is a case of a 28yo female patient, plays soccer not professionally, fell and sustained a grade IIIB AC joint dislocation with a severe horizontal instability component. In all my AC joint patients I explain the natural history of the lesion and the good functional results obtained in many cases with a conservative approach. The only patients that undergo surgery are the ones who actually choose this treatment. She was in a lot of pain and didn’t want to risk the need to undergo a more invasive surgery in a later stage if pain and dysfunction remained after 6 weeks. Her CC distance was approximately 2 times the healthy side in a zanca view and the axillary velpeau showed a completely posteriorly displaced clavicle.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

What specific patient positioning and surgical setup do you find most conducive to performing the "Closing the Circle" technique effectively?

This is a technique performed completely open, we stopped doing the “arthroscopic-assisted” part of the surgery to control coracoid drilling and implant positioning. This means that in this technique the coracoid drilling and anchor placement are performed under fluoroscopic visualization. To optimize this step we should be able to obtain a “zanca view” in the OR. The patient should be positioned in a lazy beach chair and the scapula should be completely free. Scapula mobilization can also aid in a correct reduction intraoperatively. We find that using a mechanical arm-holder makes the reduction easier.

What are some common challenges or pitfalls encountered during the procedure, and how do you navigate them to ensure optimal outcomes?

In my opinion the most challenging but also key points are the following:

1 Make sure to properly deliver the all-suture anchors well underneath the inferior cortex of the coracoid. The anchor has to go all the way through the inferior cortex so it can properly deploy as a button;

2 Reference your sutures so that you can do a proper suture management and know which sutures come from which anchor;

3 Use a nitinol wire to shuttle the sutures through the drill holes. Sometimes you have to be patient and persistent to find the nitinol underneath the clavicle or in the posterior hole of the acromion. Using a small hemostat clamp to gently dissect the soft tissues and your tridimensional spatial orientation can be helpful.

4 Avoid extensive effort to hold the reduction. Just use an arm holder to shrug the shoulder while you’re tying the knots of the construct.

Your postoperative rehabilitation protocol emphasises early mobilisation. Could you explain the rationale behind this approach and its impact on patient recovery?

We are big fans of early mobilization. Generally, all our patients start moving early but in a controlled manner. This technique is used to treat acute dislocations, so conceptually this is just a temporary construct to allow proper function while the anatomic structures heal. In the first weeks we allow mobilization in a ROM that doesn’t particularly stress the AC joint. We focus on mobilization below the shoulder level and avoid adduction, specially against any resistance. We believe that it minimizes the chance of rotation deficits after surgery. Also, from a psychological point of view, this actively includes the patient in the rehabilitation process since day 1.

How does your technique compare to other existing methods for AC joint stabilization in terms of efficacy, complication rates, and long-term outcomes?

In order to answer this I would have to have done a comparative clinical study or at least a systematic review comparing the different techniques. Unfortunately I do not have that specific data yet. But let’s talk again in a couple of years!

Considering the complexity of AC joint injuries, how feasible do you think your technique is for adoption in various healthcare settings, including those with limited resources?

Well, the fact that all the arthroscopic setting gear is out of the way makes this technique more feasible to the non-arthroscopic surgeon and considerably cheaper. The all-suture anchors are available in almost every country, and the buttons on top of the clavicle can be easily replaced by a small low profile 1/3 tubular plate if needed. No need for specific drills, drill-guides or special instrumentation.

Have you collaborated with other institutions or researchers to further study the effectiveness and refinement of your surgical technique?

We’re currently starting a collaboration with Instituto Superior Técnico (IST) in Lisbon and Universidade do Minho in Braga to further study the biomechanics and mid-term clinical results of this technique. These studies are part of my PhD project.

What are your aspirations for the future development and refinement of the "Closing the Circle" technique, and do you envision any adaptations or modifications based on ongoing research or clinical feedback?

We’ve been adapting the technique to a point in which I honestly think that there is not much more to improve. I’m a huge fan of small incisions/minimally invasive surgery, so in each patient I keep pushing for a smaller incision, just to keep it aesthetically more pleasant. The one thing that would make the technique more easy is the shuttle system.The nitinol wire is fragile and sometimes not easy to find in the soft tissues surrounding the joint. So if we find a way to improve this it will definitively positively impact the surgical moment.

We would like to thank Ana Catarina Ângelo for their time and insight into orthopaedic excellence.

Ana Catarina Ângelo, MD.

Ana Catarina Ângelo is a Shoulder and Elbow Orthopedic surgeon based in Lisbon, Portugal, she is co-founder of SHOULDER.PT and member of the shoulder and elbow units of Hospital dos SAMS de Lisboa and Hospital CUF Tejo in Lisbon, Portugal. She completed her master's degree in Medicine in 2011 at Faculdade de Medicina de Lisboa, Universidade de Lisboa, and her orthopedics and traumatology residency in Centro Hospitalar de Lisboa Ocidental. During residency she completed international fellowships in shoulder and in elbow surgery centers in France and Belgium. Between 2014 and 2019 she was actively involved in the academic training of medical students from NOVA medical school, in Lisbon.

National and international lecturer, with several communications as invited faculty in national and international events. In the last 5 years has been devoted to clinical and biomechanical investigation in shoulder surgery, with several papers published in scientific peer-reviewed national and international journals.

Scientific reviewer for several international peer-reviewed Q1 papers including AJSM, OJSM, JSES, KSSTA, JEO and Clinical Biomechanics since 2017.

She is an active member of the Portuguese Society of Shoulder an Elbow surgery, the European Society for Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy (ESSKA) since 2017, invited member of the communication committee of the European Shoulder Associates (ESA) between 2020-2022 and current member of the ESSKA-ESA scientific committee. Since 2021 Ana Catarina Ângelo has become an active member of the International Society of Arthroscopy Knee Surgery and Orthopedic Sports Medicine (ISAKOS) and a current member of the ISAKOS Communication committee. Since 2022 she has also become an ordinary member of SECEC and was elected member of the SECEC membership committee in 2023.

To download this issue of On The Podium, click below.

Sign up to On The Podium. The latest insights and inspiration from orthopaedic specialists around the globe sent straight to your inbox.

On The Podium

The newsletter brought to you by OrthoSpaceX

| Engage with Orthopaedic Leaders | Exclusive orthopaedic insight | |

| Stay Ahead in Orthopaedic Advancements | Uncover Surgical Innovations | |

| Empower Your Orthopaedic Knowledge | Unlock the Minds of Orthopaedic Specialists |